When a pharmaceutical company changes even a small part of how a drug is made - like swapping out a mixer, moving a step to a different room, or using a new supplier for an ingredient - it’s not just an internal operational tweak. It’s a regulatory event. Under U.S. law, every manufacturing change must be evaluated, classified, and reported to the FDA. Get it wrong, and you could face a warning letter, a product recall, or even a shutdown. This isn’t about bureaucracy. It’s about making sure the medicine you take today is exactly the same as the one you took last month - in strength, purity, and safety.

Why Manufacturing Changes Matter

Every drug on the shelf has been approved based on a specific set of conditions: the exact formula, the equipment used, the facility where it’s made, and the process steps that turn raw materials into a finished pill or injection. Once approved, those conditions become part of the drug’s legal identity. Change any of them, and you’re technically making a new product - even if the final pill looks identical. The FDA doesn’t want companies guessing whether a change is safe. That’s why there’s a strict system in place to classify every change based on risk. The goal isn’t to stop innovation. It’s to make sure that when you do change something, you’ve proven it won’t hurt patients. A 2022 FDA report showed that 22% of all warning letters issued that year were tied to improper handling of manufacturing changes. Of those, nearly 40% involved equipment swaps that were misclassified as minor when they were actually major.The Three Tiers of FDA Change Classification

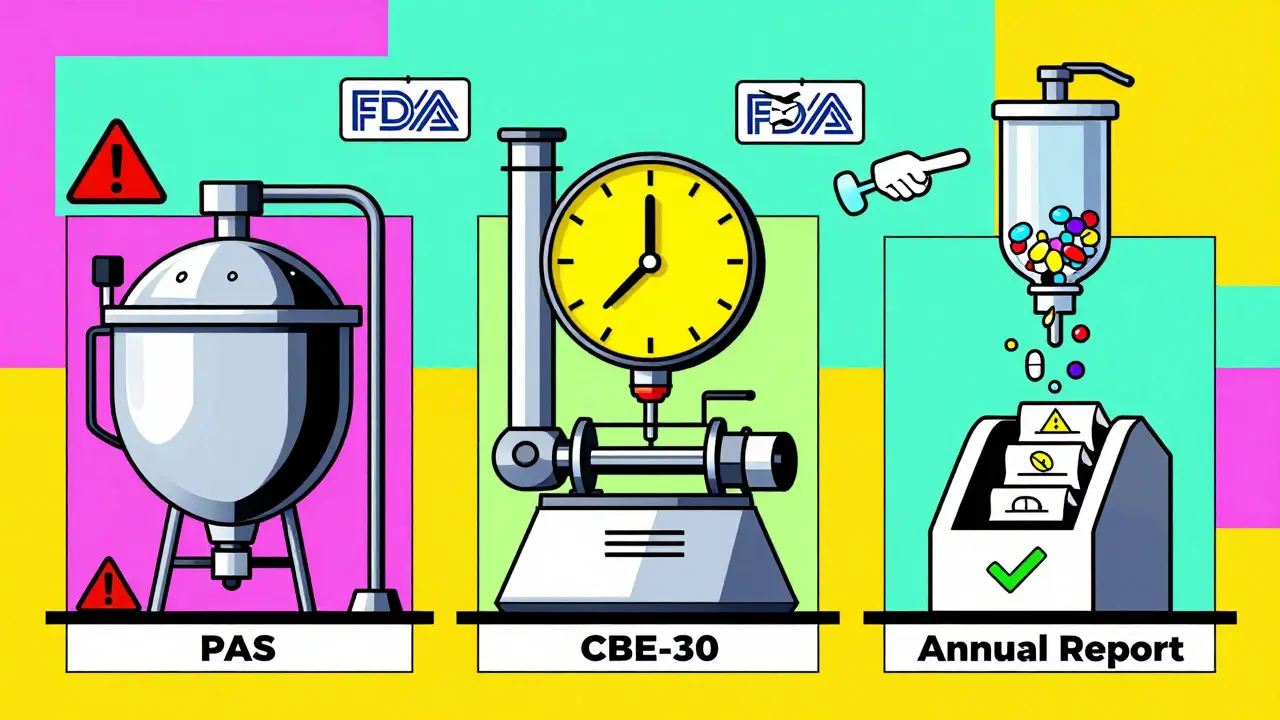

The U.S. system breaks manufacturing changes into three clear categories. Each has its own rules for notification, approval, and timing.- Major Changes (Prior Approval Supplement - PAS): These are changes with a high risk of affecting the drug’s safety or effectiveness. Examples include switching the synthetic pathway for the active ingredient, moving production to a new facility, or changing equipment that controls critical process parameters like temperature or pressure. For these, you must get FDA approval before you start making the changed product. There’s no going ahead and asking later. One company, Apotex, got a warning letter in 2019 for exactly this - they moved a key step to a new line and called it a moderate change. The FDA said it was major. They had to pull batches off the market.

- Moderate Changes (Changes Being Effected in 30 Days - CBE-30): These are changes that could affect quality but are considered lower risk. Examples: replacing a tablet press with an identical model from the same manufacturer, updating software on a filling machine, or changing the packaging material to something with the same chemical properties. You can start making the change after you submit the notification, but you must wait 30 days before distributing the product. This gives the FDA time to review. If they object, they can stop you. In 2023, Lupin Pharmaceuticals got a warning letter for starting a lyophilizer (freeze-dryer) replacement without waiting - even though they submitted the CBE-30, they didn’t wait the full 30 days.

- Minor Changes (Annual Report): These are low-risk changes that don’t impact quality. Think: changing the location of a non-critical labeling step within the same building, or switching to a different brand of the same grade of cleaning solvent. You don’t need to notify the FDA ahead of time. Just document it and include it in your annual report, which is due within 60 days after your application’s anniversary date.

How to Know Which Category Your Change Belongs To

The hard part isn’t knowing the rules - it’s knowing which rule applies to your specific change. The FDA’s 2021 guidance for biologics gives a helpful table listing common changes and their recommended categories. But real-world situations are messier. A senior regulatory affairs specialist at a mid-sized generic company told a Reddit thread in 2023 that classifying a tablet press replacement took their team 37 hours. Why? Because the API’s particle size distribution was borderline. Was the new machine capable of the same result? They had to run comparative batch data, validate the process again, and get input from quality, manufacturing, and validation teams. That’s not unusual. The key is risk assessment. The FDA expects you to use tools like Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA) - a method from the Parenteral Drug Association’s Technical Report No. 60 - to score each change. Ask: What could go wrong? How likely is it? How bad would the impact be? If the risk is high, treat it as a PAS. If it’s low, it might be annual report material.

Equipment Changes: The Most Common Pitfall

Equipment swaps cause more regulatory headaches than any other type of change. Why? Because companies assume “same machine, same result.” But the FDA doesn’t see it that way. According to FDA’s 2022 guidance, “equivalent” means three things: same principle of operation, same critical dimensions, and same material of construction. If you replace a stainless steel mixer with a plastic one - even if it’s the same size and speed - it’s not equivalent. Plastic can absorb compounds, which changes the product. That’s a PAS. Even swapping a mixer from one vendor to another can trigger a PAS if the impeller design or agitation pattern differs. One company replaced a mixer and thought they were fine because the RPM was the same. But the new mixer created more shear force. That altered the crystal structure of the API. The batch failed dissolution testing. They had to recall 12,000 bottles.Global Differences: FDA vs. EMA vs. Health Canada

If you sell drugs outside the U.S., you’re dealing with different rules. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) uses a three-tier system too, but it’s labeled differently: Type IA (minor), Type IB (moderate), Type II (major). The big difference? Timing. The FDA lets you start a moderate change after filing the CBE-30, as long as you wait 30 days. The EMA says no - you must wait for approval before starting a Type IB change. No “do and tell.” You have to ask and wait. Health Canada uses Level I (prior approval), Level II (notify and wait), Level III (annual report). It’s similar to the FDA, but the thresholds for what counts as “major” aren’t always aligned. A change that’s minor in the U.S. might be moderate in Canada. That’s why global companies often design their internal systems to follow the strictest standard - usually EMA or Health Canada - to avoid surprises.What Happens If You Get It Wrong

The consequences aren’t theoretical. In 2023, the FDA issued four warning letters specifically for misclassified equipment changes. One was to a company that replaced a sterilizer without a PAS. The product was already in distribution. The FDA ordered an immediate recall. The company lost over $3 million in inventory and faced a six-month delay in launching a new product line. Beyond recalls, there’s reputational damage. Regulators track repeat offenders. If you’ve had two warning letters for change control failures in three years, your next inspection becomes a full audit. Every batch, every document, every validation report gets pulled.

How to Build a Strong Change Control System

Large companies like Pfizer use internal risk-scoring tools - sometimes 15-point checklists - to classify changes before they even reach regulatory affairs. They score factors like:- Impact on critical quality attributes (CQAs)

- Stage of process validation

- Historical performance of the equipment

- Change complexity and number of variables involved

The Future: Harmonization and Real-Time Data

The industry is moving toward more alignment. The ICH Q12 guideline, adopted in 2020, encourages companies to use lifecycle management and risk-based approaches. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance pushes even further - suggesting companies use quality risk management (ICH Q9) to justify change classifications. Pilot programs by six major pharma companies in 2022-2023 showed that using real-time process data - sensors monitoring temperature, pressure, moisture - can reduce the need for lengthy stability studies. If you can prove the process is in control, regulators are more willing to accept lower-tier reporting. But here’s the catch: this only works if your data is reliable, your systems are validated, and your team knows how to interpret it. For now, the safest path is still the old one: classify carefully, document thoroughly, and never assume a change is minor until you’ve proven it.Final Takeaway

Manufacturing changes aren’t about making things faster or cheaper. They’re about protecting patients. Every time you alter how a drug is made, you’re changing the foundation of its safety. The regulatory system exists to make sure that change doesn’t come at a cost. If you’re in pharma - whether you’re in quality, manufacturing, or regulatory affairs - treat every change like a potential patient risk. Use data, not gut feeling. Ask for help if you’re unsure. And never skip the documentation. Because when the FDA comes knocking, they won’t care how busy you were. They’ll only care whether you followed the rules.What happens if I make a manufacturing change without notifying the FDA?

If you make a major or moderate change without the required FDA notification or approval, you’re distributing an unapproved product. This can trigger a warning letter, product recall, or even a court order to stop distribution. In 2023, the FDA issued four warning letters specifically for companies that started equipment changes without waiting for approval or the required 30-day waiting period. The financial and reputational damage can be severe.

Can I classify a change as minor just to avoid paperwork?

No. Intentionally misclassifying a change - especially a major one - as minor is considered regulatory fraud. The FDA has tools to detect this, including batch testing, inspection records, and whistleblower reports. Companies that do this face not just fines, but criminal liability. In 2019, Apotex received a warning letter after the FDA found they had misclassified a major process change as moderate. They had to recall over 200,000 units.

Do I need to re-validate the entire process after every equipment change?

Not always. For minor changes, no. For moderate changes, you typically need to run three consecutive batches showing the product still meets all critical quality attributes (CQAs). For major changes, full process validation is required. The key is demonstrating comparability - that the product made before and after the change is the same in safety and effectiveness. This is done through statistical analysis of data from both versions.

What’s the difference between a CBE-30 and a PAS?

A CBE-30 lets you start making the change after you file the notice, but you must wait 30 days before shipping the product. The FDA can still stop you during that window. A PAS requires FDA approval before you make any change or ship any product. PAS is used for major changes - like new facilities or altered active ingredient synthesis - where the risk to product quality is high. CBE-30 is for moderate changes, like replacing equipment with an equivalent model.

How long does it take to get FDA approval for a PAS?

The FDA has 180 days to review a Prior Approval Supplement. However, many are approved faster - often in 60 to 90 days - if the submission is complete and well-supported with data. Delays usually happen when the FDA requests additional information or questions the risk assessment. Planning ahead and using early consultation can reduce this timeline.

Lynsey Tyson

December 19, 2025 AT 14:55Just read this after a 14-hour shift and I’m exhausted just thinking about all the paperwork. One tiny switch in a mixer and suddenly you’re drowning in forms? I get why it’s needed, but wow. My team spent three weeks just arguing over whether a new label printer counted as minor or moderate. We ended up filing a CBE-30 just to be safe. No one sleeps well anymore.

Dikshita Mehta

December 21, 2025 AT 12:31As someone who works in pharma QA in India, I can confirm this is global. EMA’s Type IB rules are even stricter than FDA’s CBE-30. We once delayed a change for 11 weeks because we had to submit a full comparability package for a new autoclave. The FDA might let you proceed after 30 days, but EMA? Not until they say yes. It’s frustrating, but honestly? Better safe than sorry when patients are involved.

Gloria Parraz

December 22, 2025 AT 23:11Let me tell you about the time we replaced a stirrer and didn’t catch the shear difference until batch #3 failed dissolution. $2.3 million gone. No recall notice. No warning letter. Just silence from the FDA until the customer complained. That’s when the audit team showed up. I still wake up sweating thinking about it. Don’t assume ‘same specs’ means ‘same result.’ The API doesn’t care what your spreadsheet says.

Nicole Rutherford

December 23, 2025 AT 03:28Of course they’re cracking down. Big Pharma is just trying to cut corners so they can raise prices again. They don’t care if your medicine works-they care if it’s cheaper to make. That’s why they classify everything as ‘minor.’ They think we’re stupid. But the FDA’s got eyes everywhere. And if you think you’re clever for skipping the PAS, you’re just buying yourself a one-way ticket to a federal courtroom.

Mark Able

December 24, 2025 AT 07:57Wait, so if I change the color of the cleaning brush from blue to green, is that a PAS? Because my buddy’s plant did that last week and now HR says they’re ‘reviewing compliance.’ Are we seriously regulating brush colors now? I swear, if this keeps up, we’ll need a PhD just to refill the coffee machine.

Dorine Anthony

December 26, 2025 AT 05:31I’ve been in this industry for 18 years. I’ve seen warning letters, recalls, shutdowns. The one thing that never changes? The people who think ‘it’s just a small change’ are the same ones who end up on the front page of Pharma Today. Don’t be that person. Document. Validate. Ask twice. Sleep better.

Janelle Moore

December 26, 2025 AT 17:22They’re using this to track us. The FDA, the WHO, the big pharma CEOs-they’re all connected. Every change you report? It’s fed into a database that links to your health records. They’re building a profile on every patient who takes these drugs. That’s why they make you wait 30 days. To see if you get sick. Don’t sign anything. Burn the forms. This isn’t regulation-it’s control.

Henry Marcus

December 27, 2025 AT 00:39Let’s be real-this whole system is a Rube Goldberg machine built by overworked bureaucrats who’ve never held a tablet in their hands. One company replaced a mixer with a ‘similar’ one, and now they’re facing a recall because the new one had a slightly different blade angle? That’s not science-that’s witchcraft. They’re punishing innovation under the guise of safety. And don’t get me started on the ‘annual report’ loophole-what’s that, a tax write-off for laziness? The system’s broken, and nobody’s got the guts to fix it.