When a senior experiences chronic pain-whether from arthritis, nerve damage, or cancer-it’s tempting to reach for opioids. They work. But for people over 65, the risks aren’t just higher-they’re often invisible until it’s too late. A 70-year-old taking oxycodone isn’t just a smaller adult. Their body processes drugs differently. Their kidneys slow down. Their liver can’t clear toxins as fast. They’re likely on five other medications. And even a small dose can lead to confusion, falls, or breathing problems that never show up on a chart until it’s an emergency.

Why Seniors Need Different Opioid Rules

Opioids don’t age like wine. They age like milk left out in the sun. As people get older, their body changes in ways that make standard adult doses dangerous. Kidney and liver function drop by 30-50% after age 65. Body fat increases while muscle mass declines, which means drugs like fentanyl or morphine can build up in fatty tissue and linger longer than expected. That’s why experts like the American Geriatrics Society and the CDC now say: start low, go slow.For someone who’s never taken an opioid before, the right starting dose is 30-50% of what you’d give a 40-year-old. That means 2.5 mg of oxycodone, not 5 mg. Or 7.5 mg of morphine, not 15 mg. Many doctors still start with pills cut in half. That’s good. But even that might be too much for frail seniors over 80. Liquid forms-elixirs-are often safer because you can give 1.25 mg or even 0.625 mg precisely. No guessing. No cutting pills.

What Opioids to Avoid Completely

Not all opioids are created equal for seniors. Some are outright dangerous.Meperidine (Demerol) is banned in older adults. It turns into a toxic metabolite called normeperidine that builds up in the brain and causes seizures and severe confusion. Even a few doses can trigger delirium.

Codeine is another no-go. It’s a prodrug-it needs to be converted into morphine by the liver. But many seniors have a genetic variation that makes them poor converters. Others convert it too fast. The result? Either no pain relief… or a fatal overdose.

Methadone is risky because its long half-life means it can pile up over days. It also messes with heart rhythms. Even experienced pain specialists avoid it in older patients unless there’s no other option.

Tramadol and tapentadol sound safer because they’re weaker, but they carry hidden dangers. Both can cause serotonin syndrome when mixed with antidepressants-something very common in seniors. One study found that tramadol was linked to more falls and confusion than morphine in elderly cancer patients.

Best Options for Seniors: Buprenorphine and Low-Dose Oxycodone

The safest choices today are low-dose oxycodone and transdermal buprenorphine.Oxycodone immediate release (IR) is still widely used because it’s predictable. It wears off in 4-6 hours, so you can adjust quickly if side effects pop up. Start at 2.5 mg every 6 hours. If pain isn’t controlled after 48 hours, increase by 25%. Never rush.

Buprenorphine patches (like Butrans) are gaining favor because they’re gentler. Unlike full opioid agonists, buprenorphine is a partial agonist-it doesn’t fully turn on the brain’s opioid receptors. That means less respiratory depression, less constipation, and less risk of overdose. A 2024 study from the American College of Osteopathic Family Physicians found that low-dose buprenorphine (10 mcg/hour) caused no drowsiness or confusion-even when paired with low-dose oxycodone for breakthrough pain. That’s rare.

And here’s the kicker: buprenorphine doesn’t need to be titrated as aggressively. You can leave the patch on for a week. No daily dosing. No missed pills. That’s a huge win for seniors with memory issues or caregivers managing multiple meds.

What About Non-Opioid Options?

Many doctors push non-opioids first. But for many seniors, those alternatives don’t work well-or come with their own dangers.NSAIDs like ibuprofen or naproxen? They’re fine for a few days during a flare-up. But long-term use increases the risk of stomach bleeds, kidney failure, and heart attacks-all more common in older adults. The Northwest PA In Guidance recommends limiting NSAIDs to 1-2 weeks max.

Gabapentin and pregabalin (gabapentinoids) are often used for nerve pain. But a 2023 JAMA study showed they only reduce pain by about 1 point on a 10-point scale-barely better than placebo. Worse, they cause dizziness, drowsiness, and falls. One in five seniors on gabapentin ends up in the ER after a fall.

Acetaminophen (Tylenol) is safer than NSAIDs, but it’s not harmless. The max daily dose for seniors is 3 grams. For frail patients over 80 or those who drink alcohol, it’s 2 grams. Liver damage can sneak up quietly.

Physical therapy, heat/cold therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy for pain (CBT-P) are underused but highly effective. They don’t replace opioids for severe pain-but they help reduce the dose needed. A senior who walks 15 minutes a day with a walker may need 30% less opioid than one who stays in bed.

Monitoring Is Non-Negotiable

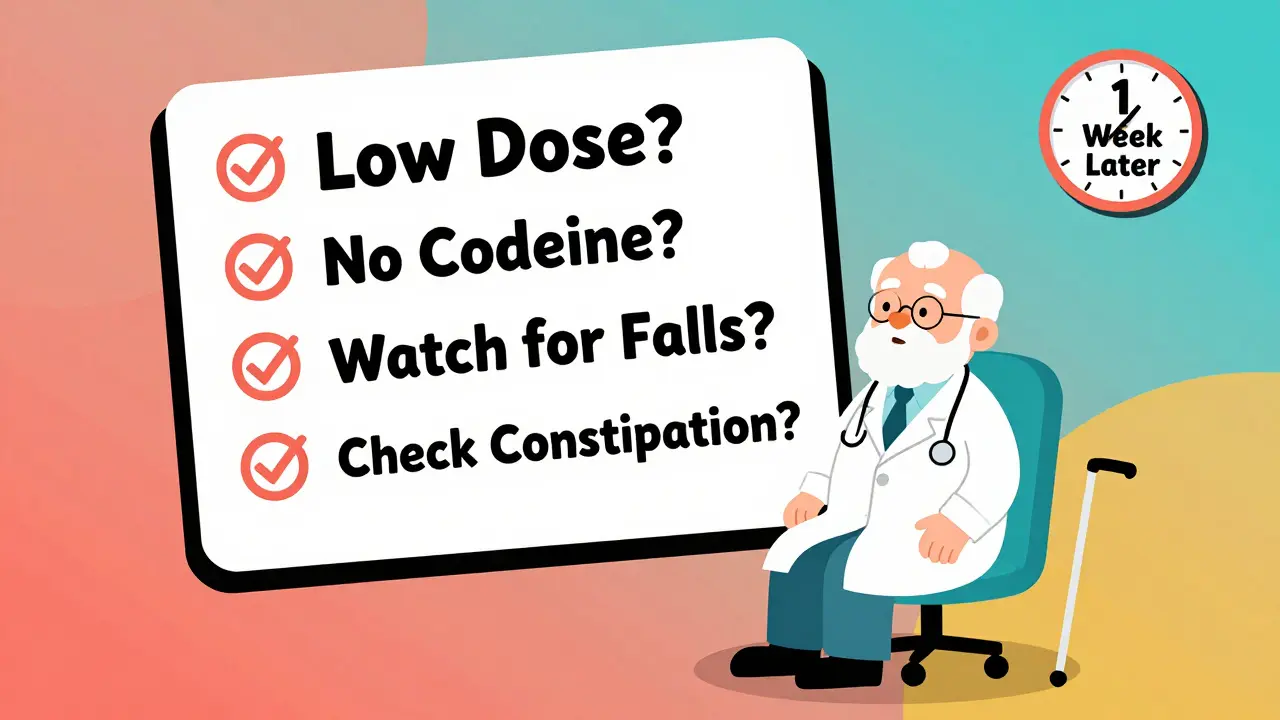

Starting opioids isn’t the hard part. Keeping seniors safe while they’re on them is.Every senior on opioids needs a written plan. Not just a prescription. A plan. That means:

- Setting clear goals: “I want to walk to the mailbox without pain” or “I want to sleep through the night.”

- Checking in every 1-2 weeks for the first month. Then monthly.

- Asking: Are you confused? Dizzy? Constipated? Falling more?

- Testing for constipation-because it’s the most common side effect, and it’s often ignored until it’s an emergency.

- Watching breathing: Especially if they have sleep apnea, COPD, or are overweight.

- Doing urine drug screens every 6-12 months to check for other substances.

And if the patient is on opioids for more than three months? You need a signed treatment agreement. Not to scare them. To make sure they understand the risks and the plan.

The Big Mistake: Applying One Rule to Everyone

In 2016, the CDC released guidelines that said: “Don’t prescribe more than 90 morphine equivalents per day.” That sounds reasonable. Until you realize it was never meant for cancer patients, hospice care, or people with severe chronic pain.What happened? Doctors started refusing opioids to seniors with advanced cancer-because they were afraid of hitting the 90 MME cap. But cancer pain is different. It’s often severe. And opioids are the most effective treatment. A 2023 JAMA study found that after the 2016 guidelines, doctors switched seniors from morphine to tramadol and gabapentin. Result? More pain. More falls. More confusion.

The CDC fixed this in 2022. They said: “Don’t apply these rules to people with cancer, palliative care, or end-of-life needs.” But many doctors still don’t know. Or they’re scared to break the old rules.

Here’s the truth: For a senior with metastatic bone cancer, 120 MME a day might be perfectly safe-if they’re monitored, their family is involved, and their pain is improving. The goal isn’t to hit a number. It’s to help them live.

What Families Should Ask

If your parent or grandparent is being prescribed opioids, ask these five questions:- Is this the lowest possible starting dose?

- Are we avoiding meperidine, codeine, or methadone?

- Will we use a liquid form if the dose needs to be very small?

- What are we watching for each week? (List: confusion, falls, constipation, breathing)

- When will we stop or reduce this if it’s not working?

Don’t be afraid to push back. Many seniors are undertreated because doctors are too afraid of opioids. But the real danger isn’t the drug-it’s the silence around it.

Looking Ahead: Better Tools Coming

The future of senior pain care isn’t just about safer opioids. It’s about smarter choices.Pharmacogenetic testing is starting to show promise. Some seniors have genes that make them process opioids too slowly or too fast. Testing can tell you which drug will work best-before you even start.

Nerve blocks and spinal cord stimulators are becoming more common for chronic pain. They don’t require daily pills. And cognitive behavioral therapy for pain (CBT-P) helps seniors reframe how they think about pain-reducing reliance on meds.

But for now, the best tool is still simple: know the patient. Know the dose. Monitor closely. No algorithm, no guideline, no app can replace a doctor who listens, checks in, and adjusts.

Can seniors safely take opioids for chronic pain?

Yes, but only with extreme caution. Seniors need lower starting doses, frequent monitoring, and avoidance of dangerous opioids like meperidine and codeine. When used correctly-with regular check-ins and functional goals-opioids can improve quality of life without causing harm.

What’s the safest opioid for an elderly person?

Transdermal buprenorphine and low-dose oxycodone immediate release are currently the safest options. Buprenorphine has fewer side effects like constipation and drowsiness, and oxycodone IR allows precise, gradual dosing. Both should start at 30-50% of standard adult doses.

Why are NSAIDs risky for seniors on long-term pain meds?

NSAIDs increase the risk of stomach bleeding, kidney failure, and heart problems-all more common in older adults. They should be limited to 1-2 weeks during acute flare-ups. Long-term use is not recommended, especially when combined with other medications.

Is tramadol safe for seniors?

Tramadol is risky for seniors. It can cause serotonin syndrome when mixed with antidepressants and increases fall risk due to dizziness and confusion. Studies show it’s less effective than morphine for cancer pain and more dangerous than it appears. Avoid it unless no other option exists.

How often should a senior on opioids be checked by a doctor?

Every 1-2 weeks for the first month, then monthly. Each visit should assess pain levels, side effects (especially constipation, dizziness, confusion), mobility, and functional goals. Urine drug screens and treatment agreements are needed if therapy lasts longer than three months.

There’s no perfect opioid for seniors. But there is a right way to use them. It starts with respect-for the body’s changes, for the complexity of aging, and for the quiet dignity of someone who just wants to move without pain.

Sarah Williams

December 22, 2025 AT 18:00This is the kind of post that actually helps. I’ve seen my grandma go from barely walking to dancing at her birthday party after switching from oxycodone to buprenorphine. No more confusion, no more falls. Just quiet, steady relief.

Theo Newbold

December 23, 2025 AT 12:39The data here is cherry-picked. You ignore the fact that opioid prescribing in seniors increased hospitalizations by 22% between 2015 and 2020 according to CDC mortality data. Buprenorphine isn’t magic-it’s just the new trendy drug pushed by pharma to replace oxycodone after the crackdown. Watch the ads.

Jay lawch

December 25, 2025 AT 01:48Let me tell you something about Western medicine-they don’t care about your grandma. They want to control the narrative. Opioids are being demonized because Big Pharma wants you dependent on their expensive patches and tests. Meanwhile, in India, we’ve used turmeric, ashwagandha, and yoga for centuries to treat pain without poisoning the elderly. Why are we letting American doctors play god with our elders’ brains? They don’t even know what a real root is anymore. This whole system is a scam built on fear and profit. The real danger isn’t the drug-it’s the system that profits from it.

Michael Ochieng

December 26, 2025 AT 05:44As someone who works with immigrant families, I’ve seen this play out over and over. Grandparents in silence, afraid to say they’re in pain because they don’t want to be a burden. This post gives families the language to ask the right questions. Thank you. My uncle was on codeine for months until we switched him to liquid oxycodone-his mood improved in days. It’s not about avoiding opioids. It’s about respecting the person behind the prescription.

Erika Putri Aldana

December 27, 2025 AT 21:33So basically… don’t give old people pills unless you’re willing to babysit them 24/7? Cool. I’ll just give my dad Advil and hope he doesn’t die. 🙃

Grace Rehman

December 29, 2025 AT 07:14They say start low go slow but no one ever says stop when it’s working. We treat pain like it’s a math problem instead of a human experience. My aunt was on 2.5mg oxycodone for six months. She walked again. She baked pies. She laughed. Then the doctor said ‘we need to taper’ because ‘guidelines’. She cried. The guidelines didn’t know her. The doctor didn’t know her. But I did. Sometimes the right dose is the one that lets someone live, not just survive.

Jerry Peterson

December 29, 2025 AT 15:39I’ve been a caregiver for my dad for five years. He’s 84, has arthritis and neuropathy. We tried everything. NSAIDs gave him ulcers. Gabapentin made him fall. Tramadol? He got so confused he forgot his own name for three days. Then we tried buprenorphine patch. No drama. No daily pills. He still complains about the tape peeling off but honestly? I’d rather deal with tape than a hospital bed. This post nailed it.

Siobhan K.

December 31, 2025 AT 07:21Interesting how the CDC’s 2016 guidelines were weaponized against cancer patients. I work in hospice in Dublin. We had a woman on 180 MME daily from morphine-perfectly stable. Doctor tried to cut it to 90 ‘for safety’. She was in agony for weeks. We had to fight the charting system to restore it. Pain isn’t a number. It’s a scream in the dark. And sometimes, the only thing that quiets it is the right opioid. The real failure isn’t prescribing-it’s not listening.

Brian Furnell

January 1, 2026 AT 08:57Let’s be clear: the pharmacokinetic changes in geriatric populations are profound and non-linear. Hepatic clearance via CYP3A4 and CYP2D6 pathways declines significantly after age 65, and renal excretion of active metabolites-particularly for opioids with nephrotoxic metabolites like normeperidine-is drastically reduced. This is why the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria explicitly contraindicates meperidine and codeine. Additionally, the pharmacodynamic sensitivity of mu-opioid receptors increases with age, meaning even subtherapeutic plasma concentrations can induce CNS depression. Buprenorphine’s ceiling effect on respiratory depression and its partial agonist profile make it uniquely suited for this population. Furthermore, transdermal delivery circumvents first-pass metabolism and reduces pill burden-a critical factor in polypharmacy. The 2024 ACOFP study you cited corroborates this with a 92% reduction in sedation-related adverse events compared to full agonists. But here’s the kicker: monitoring isn’t just about vital signs. It’s about functional status. A 10-point pain scale is meaningless if the patient can’t get out of bed. You need gait analysis, MMSE, and bowel diaries. And yes, pharmacogenomics is the future-CYP2D6 poor metabolizers are 3x more likely to experience toxicity with tramadol. We need point-of-care genotyping in primary care. Not just guidelines. Evidence. Action.