The Hatch-Waxman Act didn’t just change how generic drugs get approved-it rewrote the rules of the entire U.S. pharmaceutical market. Before 1984, getting a generic version of a brand-name drug to market was nearly impossible. The FDA required full clinical trials, which cost millions and took years. Meanwhile, brand-name companies held patents that blocked anyone else from even testing their drugs. Then came the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, better known as the Hatch-Waxman Act. It wasn’t just a law. It was a deal-a fragile, brilliant compromise between drug makers who wanted to protect their profits and companies that wanted to sell cheaper versions of those drugs.

How the Hatch-Waxman Act Broke the Logjam

Before 1984, generic drug approvals were rare-fewer than 10 per year. The Supreme Court had ruled in Roche v. Bolar that testing a patented drug before the patent expired was illegal, even if it was just to gather data for FDA approval. That meant generic companies couldn’t start preparing until the patent expired. By then, the brand-name drug had already captured the market. Hatch-Waxman fixed that with one simple but powerful change: the safe harbor provision. Under 35 U.S.C. §271(e)(1), generic manufacturers could now legally make, test, and study patented drugs during the patent term-as long as the only goal was to get FDA approval. That single change cut the time to market by years.

At the same time, the Act created the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway. Instead of repeating expensive clinical trials, generic companies only had to prove their drug was bioequivalent to the brand-name version. That meant the same active ingredient, same dosage, same way it’s absorbed by the body. The FDA estimated this cut development costs by about 75%. Suddenly, it made financial sense to produce generics. By 2019, the FDA approved 771 generic drugs. Today, 90% of all prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generics.

The Patent Game: Extensions and Loopholes

The Act didn’t just help generics. It also gave brand-name companies something they desperately wanted: patent term restoration. The FDA’s approval process could take up to a decade, eating up years of a drug’s 20-year patent life. Hatch-Waxman allowed innovators to extend their patent by up to 14 years-though in practice, the average extension was just 2.6 years. That was supposed to balance the scales. But over time, drug companies learned to game the system.

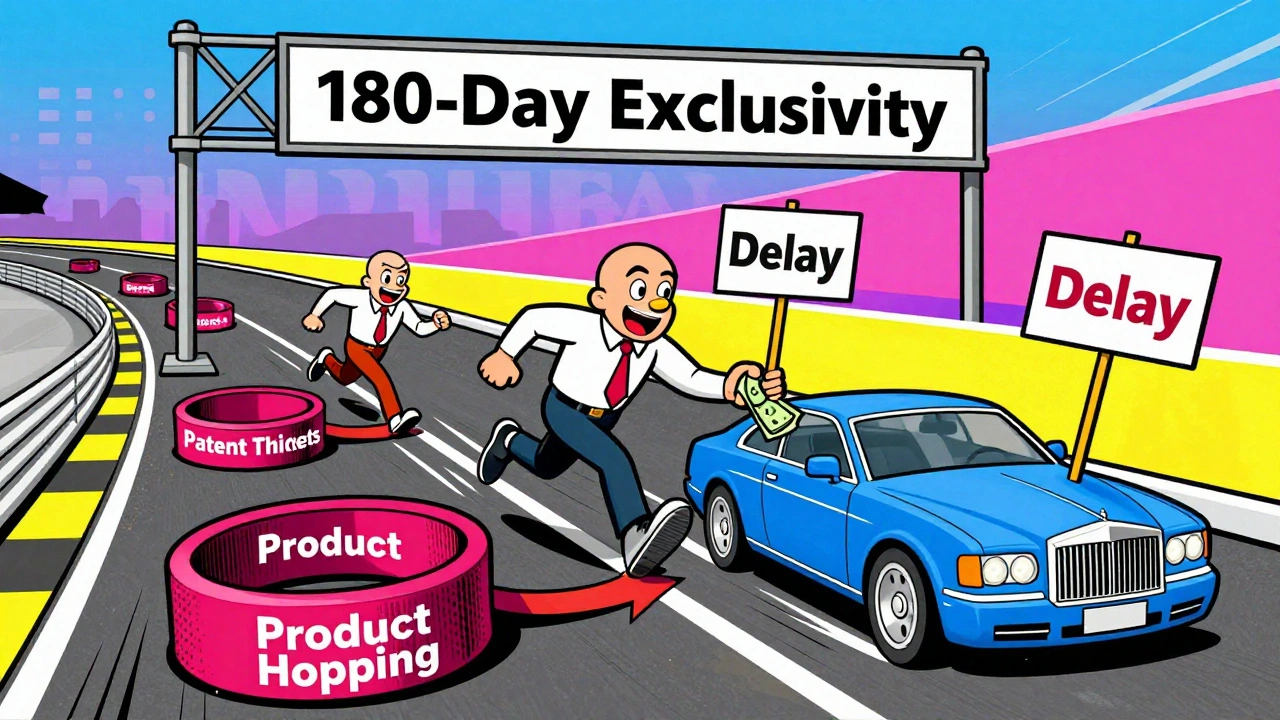

Instead of one patent per drug, companies started filing dozens. In 1984, the average drug had 3.5 patents. By 2020, it was 14. These weren’t all groundbreaking inventions. Many were minor changes-new coatings, different dosing schedules, or combinations with existing ingredients. These are called secondary patents. They don’t make the drug better, but they keep generics off the market longer. This practice, known as patent thickets, delays generic entry by an average of 2.7 years, according to Professor Robin Feldman’s research.

Another tactic is product hopping. A brand company slightly modifies its drug-say, changing from a pill to a tablet-and then pushes doctors and patients to switch. The original drug’s patent expires, but the new version gets a new patent clock. Patients end up paying more, and generics can’t enter until the new patent runs out. The FTC has documented over 260 such cases between 2010 and 2022, especially in cancer, autoimmune, and neurological drugs.

The 180-Day Exclusivity Trap

One of the most powerful tools in Hatch-Waxman is the 180-day exclusivity window for the first generic company to challenge a patent successfully. That’s the reward for taking the legal risk. The first filer gets to be the only generic on the market for six months-no competition, high prices, big profits. But here’s the twist: companies started gaming this too.

In the early 2000s, multiple generic companies would file on the same day, hoping to share the exclusivity. The FDA changed its rules to allow shared exclusivity, but that didn’t fix everything. Now, brand companies file 50 or more patents on a single drug. Each one creates a new legal hurdle. The first generic filer might challenge one patent, but if another patent is still active, they can’t launch. Meanwhile, other generics sit back, waiting. The 180-day clock doesn’t start until the first legal battle ends-sometimes years later. For blockbuster drugs, that exclusivity window has become meaningless.

Pay-for-Delay: The Secret Deals

Perhaps the most controversial loophole is pay-for-delay. Instead of fighting in court, some brand-name companies pay generic manufacturers to delay their launch. The generic gets a cut of the brand’s profits, and the brand keeps its monopoly. Between 2005 and 2012, 10% of all patent challenges ended this way. These deals cost consumers billions. In 2013, the Supreme Court ruled these agreements could be illegal under antitrust law-but didn’t ban them outright. Since then, they’ve become harder to prove, but they still happen.

One study found that pay-for-delay deals increased prescription drug spending by $149 billion annually since 2010. The 2023 Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act, passed by the House, would ban these payments entirely. If it becomes law, it could be the biggest change to Hatch-Waxman in decades.

Who Wins and Who Loses?

The numbers tell a clear story. Since 1991, Hatch-Waxman has saved the U.S. healthcare system over $1.18 trillion. Generic drugs now make up 90% of prescriptions but only 18% of drug spending. That’s a massive win for patients and insurers. But the system isn’t perfect. The top 10 generic manufacturers now control 62% of the market, up from 38% in 2000. Smaller companies can’t afford the legal battles or the 30,000-page ANDA submissions. The average cost to challenge a patent is $15-30 million. Only big players can play.

Meanwhile, brand-name companies have extended their effective market exclusivity by an average of 1.2 years beyond what the law originally intended. The average new drug now gets 13.2 years of market protection-not the 10-12 years most people assume. That’s thanks to patent extensions, thickets, and delays.

What’s Changing Now?

The FDA is trying to fix some of the worst abuses. In 2022, it issued draft guidance to stop companies from listing patents in the Orange Book that don’t qualify. The 2022 CREATES Act made it illegal for brand companies to refuse to sell samples to generic makers-something they used to do to block testing. And under GDUFA IV, the FDA aims to cut ANDA review times from 10 months to 8 months by 2025.

But the biggest threat to Hatch-Waxman isn’t from regulators-it’s from its own success. The system was designed for a simpler time, when patents were fewer and litigation was less complex. Today, the average drug faces 4.3 patent challenges. In 1984, it was 1.2. The legal system is clogged. The FDA is overwhelmed. And patients still pay too much for drugs that should be cheap.

Experts like former FDA Commissioner Robert Califf admit the original framework has been "gamed." But others, like Michael Taylor, who helped draft the law, argue that without Hatch-Waxman, we’d have seen 30-40% fewer new drugs approved since 1984. The truth is, the Act worked-but not exactly as intended. It created a system that delivers cheap drugs, but only after years of legal battles and corporate maneuvering.

The Future of Generic Drugs

Is Hatch-Waxman still relevant? In 2023, 87% of pharmaceutical executives said yes. The core idea-balancing innovation and access-still makes sense. But the tools need updating. The 180-day exclusivity window needs to be restructured. Patent listing rules need teeth. Pay-for-delay deals need a full ban. And the FDA needs more funding to keep up with the volume of applications.

Right now, the system is like a car with a great engine but rusted brakes. It moves fast, but it’s dangerous. The good news? The fixes are known. The challenge is political will. Until then, patients will keep waiting-for generics that should be available, for prices that should be lower, and for a system that was meant to serve them.

Ben Greening

December 11, 2025 AT 05:16The Hatch-Waxman Act was a masterclass in legislative compromise. It didn’t solve everything, but it created a functional equilibrium between innovation and access. The numbers speak for themselves-over a trillion dollars saved since 1991 is staggering. What’s remarkable is how the system held together for decades despite the inevitable corporate exploitation. The real tragedy isn’t the loopholes-it’s that the fixes are obvious but politically unpalatable. We know how to fix patent thickets and pay-for-delay. We just lack the will.

David Palmer

December 12, 2025 AT 05:27so like… generics are cheap but the big pharma guys just keep making tiny changes to the pill and calling it a new drug? lol. they’re literally just playing monopoly with our prescriptions. i paid $400 for a 30-day supply of something that should cost $5. this is insane.

Jimmy Kärnfeldt

December 12, 2025 AT 08:32It’s wild to think this law was designed in the 80s, before smartphones, before the internet, before we fully understood how complex drug development would become. The framework was brilliant for its time-like building a highway that could handle 100 cars an hour. Now we’ve got 10,000 cars trying to use it, and the exits are all blocked by toll booths disguised as patents. We don’t need to tear it down. We need to widen the lanes, add more exits, and remove the bribes at the booths. The spirit of Hatch-Waxman? Still alive. The execution? Needs a major upgrade.

Ariel Nichole

December 12, 2025 AT 15:28Really appreciate this breakdown. I didn’t realize how much the 180-day exclusivity window got twisted into a tool for delay instead of competition. It’s like giving someone a prize for finishing first… but then letting them sit on the finish line and block everyone else. The FDA’s new guidance on Orange Book listings is a good start, but it’s like putting a bandaid on a broken leg. Still, progress is progress.

john damon

December 13, 2025 AT 06:56pay-for-delay is literally bribery 🤡💸 and we let them get away with it?? this is why i hate the american healthcare system. why do we even have laws if they’re just suggestions??

matthew dendle

December 14, 2025 AT 07:51so the law was meant to lower prices but now its just a game of who can file the most patents or pay the most lawyers? wow. real innovative. guess i shouldve majored in law instead of bio. also why is everyone so shocked? this is america. if you can exploit a loophole, you’re a genius. not a criminal.

Taylor Dressler

December 14, 2025 AT 16:04One thing often overlooked: the ANDA process isn’t just cheaper-it’s scientifically rigorous. Bioequivalence testing is incredibly precise. The FDA doesn’t just accept ‘close enough.’ They require statistical proof that the generic performs identically in the body. That’s why generics are safe, even when they’re 90% of prescriptions. The problem isn’t the science-it’s the legal and financial barriers that keep small manufacturers out. Fix the cost of litigation, not the law. That’s where the real innovation needs to happen.

Jean Claude de La Ronde

December 15, 2025 AT 22:21so hatch-waxman gave us cheap drugs… but only after 10 years of lawyers arguing over whether a coating counts as an invention? classic. we built a system that rewards patience and lawyers more than patients. and now we’re surprised when the system breaks? lol. next they’ll patent the color of the pill.